May 10, 2023 Industry news

For more than half a century, GS1 barcodes have been transforming the way we work and live. Since being adopted by the US grocery industry in 1973, barcodes have propelled global commerce into a whole new era – an era of control, traceability, data-informed management and customer focus, all powered by a 13-digit GTIN.

GS1 barcodes are now scanned more than ten billion times each day and, whether in a store, warehouse, hospital or construction site, are helping more than two million organisations worldwide to uniquely identify, describe and track anything, creating greater trust in data for everyone.

However, despite their incredible impact and the role they have played in shaping the modern world, research we conducted to celebrate the barcode's 50th birthday revealed that remarkably few know the story behind what is undeniably one of the most significant innovations of the 20th century.

Norman Joseph Woodland

This largely forgotten story began all the way back in 1949, when inventor Norman Joseph Woodland drew the world’s first barcode in the sand of a Miami beach.

Woodland was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on 6 September 1921. After graduating from High School, he served in the United Sates military during World War II as a technical assistant with the Manhattan Project.

Norman Joseph Woodland

After completing his military service, he graduated from the Drexel Institute of Technology (now known as Drexel University) in 1947 with a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering (BSME) and spent the next two years lecturing at the University while also perfecting a system for efficiently delivering elevator music.

His system, which recorded fifteen simultaneous audio tracks on 35-millimeter film stock, was less cumbersome than existing methods, which relied on LPs and reel-to-reel tapes.

Woodland had planned to launch it commercially but his father, who had come of age during the prohibition era, forbade it, believing that elevator music was controlled by the mob.

In 1948, Woodland’s friend and fellow Drexel graduate student, Bernard Silver, overheard a conversation between a supermarket executive and the dean of engineering. The executive wanted to know if the engineering department could develop a system for boosting supermarket efficiency by automatically capturing product information at the point of sale. While the dean turned the request down, the concept piqued Silver’s interest and he began discussing ideas with Woodland who was confident he could create a viable solution.

Lines in the sand

Woodland and Silver’s initial idea involved printing product information in fluorescent ink and reading it with ultraviolet light, although this soon proved unworkable.

Woodland however remained convinced that a solution was close at hand, so he quit graduate school to focus on its development. He moved to his grandparents’ home in Miami Beach Florida and spent the winter of 1948-49 in a chair in the sand, mulling it over.

He soon realised that in order to represent information visually he would need a code, just like the Morse code he had learned during his time as a Boy Scout.

One day, while sat on the beach, he began trailing his fingers through the sand. In that moment he realised that, just as Morse Code was used to communicate information with sound, finding a way to visually represent its dots and dashes offered the perfect solution to the store checkout conundrum.

What I’m going to tell you sounds like a fairy tale. I poked my four fingers into the sand and for whatever reason — I didn’t know — I pulled my hand toward me and drew four lines. I said: ‘Golly! Now I have four lines, and they could be wide lines and narrow lines instead of dots and dashes.’”

Normal Joseph Woodland

From a 1999 interview with Smithsonian magazine

From this realisation, he developed a concept for a two-dimensional, linear Morse code and shared his idea with Silver. The pair then applied for a patent on 20 October 1949. Titled “Classifying Apparatus and Method”, the patent was awarded in 1952, covering both linear barcode and circular bullseye designs.

Ahead of its time

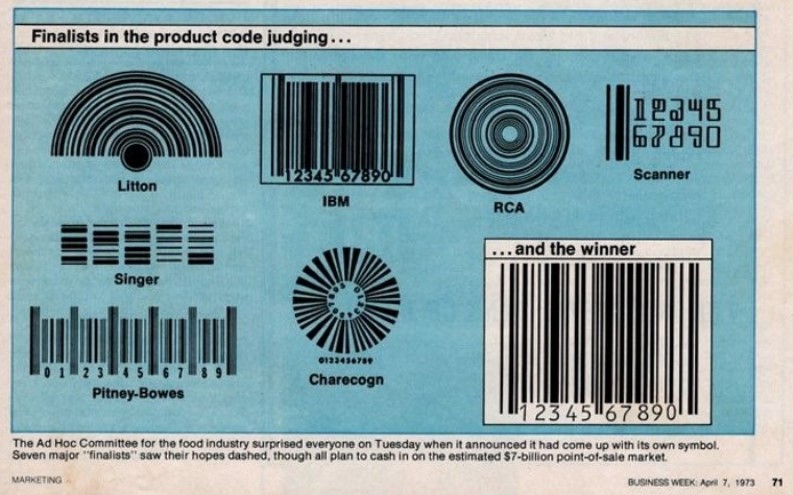

Woodland actually favoured the bullseye design over the iconic black and white lines we know today, arguing that a circular pattern would be more efficient as it could be scanned from any orientation.

However, that method required an immense scanner equipped with a 500-watt light, making it too expensive and impractical for commercial use.

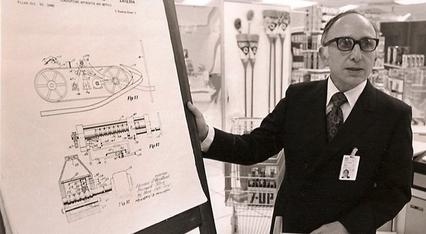

Woodland explaining his prototype scanner for products with bar codes

In 1951 Woodland began working for IBM but he still hadn’t given up on making his vision for linear morse code a reality. He and Silver continually attempted to persuade IBM to progress their concept, but the technology required to power it still wasn’t commercially viable.

The pair eventually sold their patent to the Philadelphia Battery Company (Philco) for a mere $15,000, the only money they would ever make from an invention that would one day transform global commerce.

Philco sold the patent to the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) in 1952 who did attempt to develop commercial applications throughout the 1960s until the patent expired in 1969.

Vision becomes reality

The RCA soon secured the interest of the National Association of Food Chains, who then formed the U.S. Supermarket Ad Hoc Committee to accelerate the development of a “Uniform Grocery Product Code.”

Realising that Woodland’s idea now had legs, IBM once again became interested and transferred Woodland to their North Carolina facilities where he played a vital role in developing the most important iteration of the technology; the Universal Product Code (UPC).

At the same time, laser scanning technology was rapidly improving and when Intel released the world's first commercial microprocessor in 1971, in-store barcode scanning finally became workable. Industry however still needed to agree on a common symbol for capturing all their product information.

It was Woodland’s IBM colleague, George J Laurer, who eventually turned Woodland’s original sandy rectangle of thick and thin lines into the ubiquitous design now found on more than a billion products all over the world.

Out of the seven potential designs submitted to the U.S. Supermarket Ad Hoc Committee, Laurer’s design was clearly the most practical and was selected by industry leaders on 3 April 1973. This was in no small part thanks to Alan Haberman, a supermarket executive and founding member of the Universal Product Council - the organisation that would eventually become GS1 - who worked tirelessly to promote and popularise the rectangular barcode as the industry standard.

Powering progress

Just over a year later, on June 26, 1974, a packet of Wrigley’s chewing gum sold at a Marsh supermarket in Troy, Ohio, became the first product scanned at a checkout using Laurer’s design. The barcode soon crossed the Atlantic in typically British fashion, first appearing on a box of Melrose tea bags at a Keymarkets supermarket in Spalding, Lincolnshire, in October 1979.

Today, these humble black and white lines touch almost every aspect of our lives and are used more frequently than Google. Barcodes continue to revolutionise our day-to-day in ways most do not realise – keeping our shelves stocked with products and ingredients from around the world, helping us find and buy products online, ensuring what we consume is genuine and safe, helping the NHS save time, money and lives – and much more.